Killing Your Darlings at 11 PM: How I Learned to Edit Without Mercy!

When running up against some brutal feedback and a length problem with my script, I reverted to a discipline I call "Edit Without Mercy!"

Hello, My Friends,

As kids my friends and I had one rule for our make-believe movies: Can you explain it?

It didn't matter that your car could fly, but how did it fly? Where did the wings come out? How fast did you need to go before takeoff, and how long could you stay airborne before running out of gas? Answer those questions, and you had yourself a flying car.

This single rule, created by a group of kids in 1970s New Jersey, became the foundation of everything I know about storytelling, world-building, and—as I recently discovered—surviving brutal industry feedback.

Where Imagination Begins

Happy Summer Solstice! Late June has always been special to me—not just because it marks my favorite season, but because it takes me back to those formative summers on Wood Street in Rutherford, New Jersey.

The late 1970s and early 1980s were a magical time to be a kid. Sure, I could see the Empire State Building from my bedroom window, and planes constantly roared overhead toward JFK, but Manhattan felt like another planet. Wood Street was my universe.

My crew consisted of John and Charles Spitaletta, Arnold Chan, and Danny Willis. We spent our days playing wiffle ball and manhunt, but our real passion was "making movies." This was long before cell phones or accessible video equipment, but we didn't need technology—we had something better: unlimited imagination and a willingness to commit completely to our fictional worlds.

John, who later became an advertising director, would set up our scenes and establish the physical space. My job was dialogue. I was the kid who'd stop mid-scene and say, "No, you say this..." then we'd pick up where we left off.

Our movies were ridiculous—action-heavy adventures with lots of shooting and fighting—but they taught me everything about creative problem-solving. We had no limits except one: everything had to make sense within our world's logic.

One of our most elaborate explanations involved our characters being professional athletes who played football, basketball, AND baseball. The problem? Height differences between sports. My solution: bone-stretching pills from a special doctor that would give us the 4-6 inches needed for basketball.

But in our world, there had to be consequences. Since we didn't know what bone-stretching would actually feel like, we decided the side effect would be the worst thing any kid could imagine: vomiting. All night.

I still remember sitting in the Spitaletta brothers' backyard, each of us hunched over a designated rock or bush, pretending to retch through our "treatment." We were completely serious about this absurd detail.

These experiences became my creative boot camp. We learned to build believable worlds from scratch, create compelling characters, and most importantly—make imagination feel real through logical consistency.

Looking back, I'm grateful we chose imagination over the early video games that were starting to appear. We weren't just playing games; we were living them, creating them, becoming them.

Fast Forward: When Reality Bites Back

That childhood training in creative problem-solving recently got its biggest test yet.

Quick Headcase Update:

Headcase continues to gain momentum as a TV pilot, having recently won at the Big Apple Film Festival. The festival was incredible—I connected with filmmakers sharing war stories about creating shorts and indies on shoestring budgets.

But here's the reality about film and TV: the castle walls are high, the moats are deep, and they protect the elusive agents, managers, and producers who might give new writers a real shot.

Contests provide valuable feedback and audience response data. I often pay extra for professional script coverage, and I regularly organize table reads where actors perform my work aloud.

My most recent table read, conducted via Zoom for the first time, became a masterclass in humility.

I made the mistake of asking for brutally honest feedback. Boy, did I get it.

Several actors lit me up, primarily about how Sandra and other female characters felt like "window dressing" or "accessories" to Andrew's story.

My defensive response: "Well, he's at a baseball game, but he's really working. He's not going to call Sandra mid-session with an athlete."

The criticism continued. Afterward, the event director offered this advice: "They were pretty harsh, but see if you can find any truth in it."

I could have doubled down: "What do they know? My pilot has won awards."

Instead, years of judo senseis and Buddhist masters beating the ego out of me kicked in. I chose deeper reflection over defensiveness.

The Revision Crucible

Here's my philosophy about criticism: don't listen for tone or poorly chosen words. Listen for the real message.

The real message was clear: I needed Sandra, Gina, and Lorry involved earlier in the script.

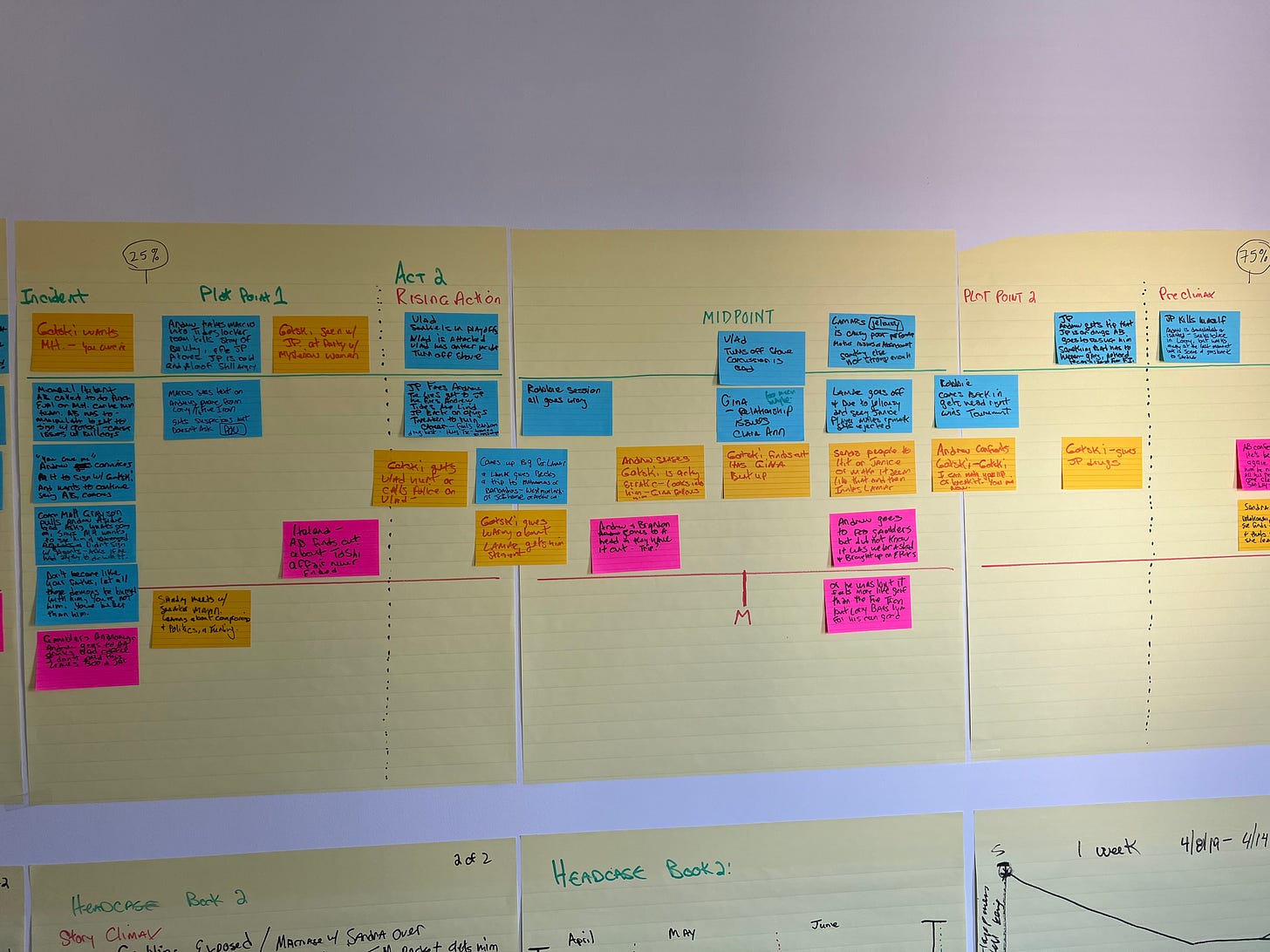

Over the weekend, I spread 3M colored index cards across a wall. Each color represented different storylines from my outline. The beauty of note cards? You can physically move scenes around to test different structures.

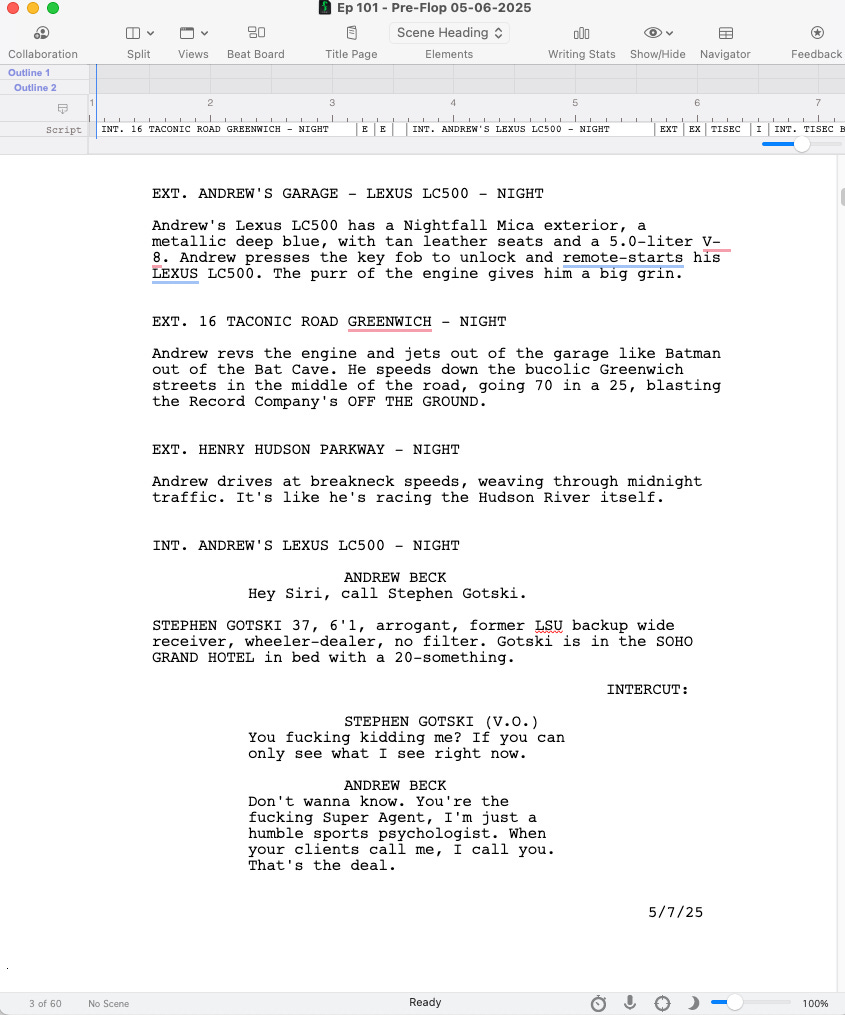

To get Sandra into the action immediately, I needed to start with a crisis. I completely restructured the timeline, moving Lamar's midnight crisis call from Chapter 8 (page 79 in the novel) to the opening scene. My original pilot focused on John Palmer's opening day meltdown—Lamar wasn't even mentioned.

This wasn't a small tweak; it was architectural surgery. But knowing my characters and story direction, I could visualize the new structure. I laid out all scenes on colored cards and rearranged them until the story flowed coherently.

The new version eliminated childhood flashbacks entirely. We meet Andrew as the man he is now, without his genesis story as setup.

Once I had the opening outlined, everything clicked. I rewrote the entire pilot in 16 hours across three days.

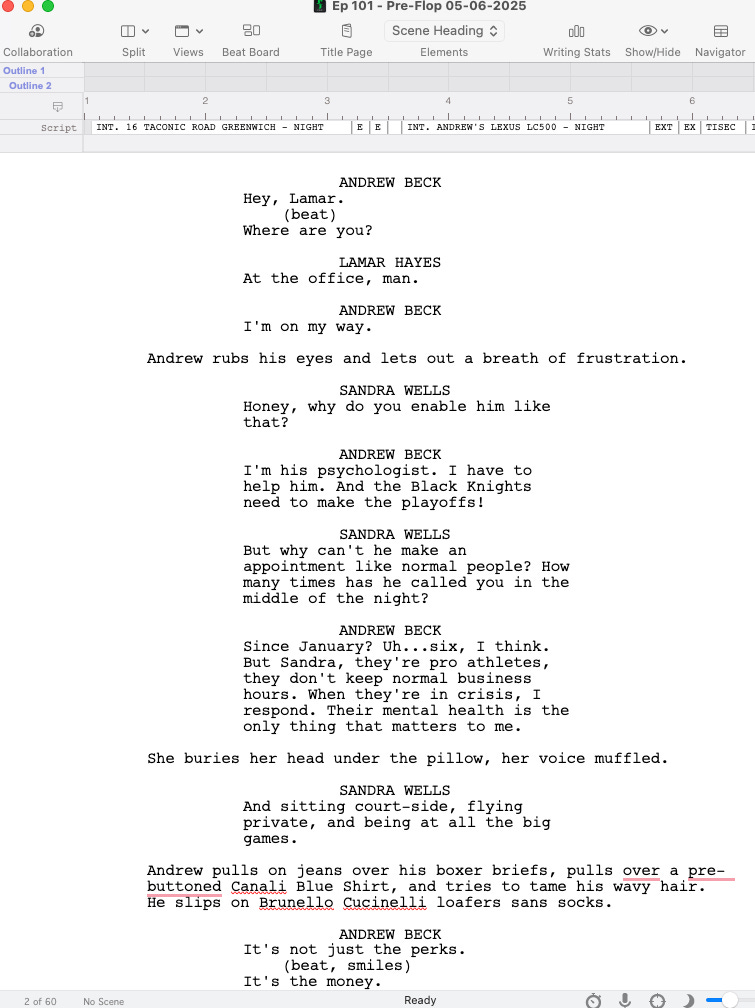

One problem: I was at 63 pages. Industry standard for TV is 60 pages (one page equals one minute of screen time). Some contests have hard 60-page limits.

The Page-Count Death Match

Getting from 63 to 60 pages became one of the hardest writing challenges I've ever faced.

Here's the problem with Final Draft screenwriting software: unlike Word or Google Docs, it handles text completely differently. It's optimized for directors and actors, which means page breaks are unpredictable. Scenes always start on new pages, leaving irregular white space. Whether you end a page with dialogue or stage direction affects everything.

I refused to cut scenes or dialogue, which left only "Action"—the directorial notes describing what's happening.

This exposed a crucial difference between novel and script writing. In novels, I can be as descriptive and verbose as I want. Readers often appreciate rich detail. In scripts? That's called "directing from the page," and directors hate it. My job is giving the essence of scenes; actors and directors decide how to bring them to life.

First, I eliminated single-word or two-word line overhangs—each represented wasted real estate. This meant "killing my darlings" without cutting actual content.

I became a ruthless "word-CFO," applying "editing without mercy." I had to detach from my creative artist self and slash the word budget to bone.

I started at 3:30 PM, expecting to finish by 6:00, hit the gym, grab dinner, and call it a night.

Nope.

Converting 60-word narrative passages to 30-40 words proved brutally difficult. It was a masterclass in concision, forcing me to ask: "Is this really necessary? Would directors and actors understand without the extra narrative?"

By 6:00 PM, I'd eliminated maybe half a page. No workout earned. I ate at my desk, exporting narrative to Google Docs and using Grammarly to rephrase everything while maintaining emotional and visual impact.

By 9:00 PM, I was getting better at cutting, more ruthless and precise. It was like moving day—that morning chachka that seems precious becomes disposable after eight hours of packing.

But I was stuck at page 61. Not a full page—nine goddamned lines holding me from victory.

Final Draft's cruelty revealed itself. I'd eliminate or reword narrative, sometimes saving two full lines, scroll to the end expecting triumph, and find those same nine lines mocking me on page 61.

By 10:00 PM, fatigue and frustration were setting in. I was down to six lines over budget. I'd only eliminated two lines of dialogue (which actually improved the scene), but I was still six lines from freedom.

Back to page 1. Again.

I removed words here and there, saving a line or two. As 11:00 PM approached, I was ready to quit for the night. Then I glanced at the page count.

60 pages.

I don't know what final edit did it—maybe changing two lines on page 20 that cascaded through the entire script—but like magic, I was there.

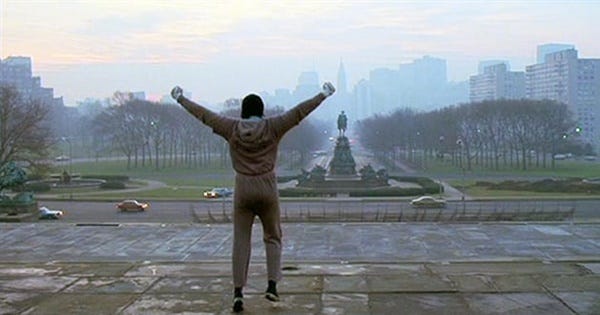

I'm not being dramatic when I say I yelled in triumph and raised my hands like Rocky on the Philadelphia Museum steps. Cutting those three pages over eight hours of non-stop editing ranks among my proudest writing moments. It topped winning awards because it was genuinely difficult and pushed me beyond my comfort zone.

Doing hard things is good for me. Pushing myself feels good. Perhaps all those years on soccer fields, wrestling mats, and judo tatamis prepared me for moments like this—doing difficult work alone, with only my conscious mind as overseer.

It was after 11:00 PM, so I couldn't share my excitement with anyone. I sat in humility and enjoyed my private victory.

But the real prize was still coming.

Industry Validation

I've been working with a Hollywood manager named Lameese. She's been incredibly generous with her time and feedback, reading multiple drafts. She was also the first to point out that my original pilot felt more like a season finale than a pilot episode.

I'm not her client, so her willingness to read my work and provide feedback deserves recognition in an industry where every manager and agent has stacks of unread scripts by their bedside.

I sent her the revision the next day. A week later, she sent a short email:

"Chris, you nailed it with the re-write. Really thought the hook and engine was clearer in this one and it no longer feels like a season finale but the setup of a show."

That was the prize. Professional industry feedback meant more than all my awards combined.

But Hollywood reality followed:

"That being said, I really can't get a lot of internal excitement right now to take on additional lower-level writers in the TV space. We're a bit full up on them and the jobs aren't really there. The market is particularly bad (as I'm sure you've heard) with selling shows unless they're from seasoned TV writers.

Should you conjure up anything in the feature world though (particularly horror, thriller, or action), feel free to reach out."

She ended with validation that made the entire struggle worthwhile:

"You have a skill that's tough to find in most writers which is the skill of re-write. 😊

I'd focus on creating a stellar spec and that could open a lot of doors."

By "spec," she meant feature film. So I'm pondering: Headcase has been a scripted audio play, TV pilot, 483-page novel, and serialized Substack story. Why not a film?

The Journey Continues

Looking back at that kid creating bone-stretching pill explanations in a New Jersey backyard, I see the same creative problem-solving muscle at work today. The tools are more sophisticated, the stakes higher, but the core challenge remains: Can you explain it?

Whether it's making flying cars believable or turning harsh feedback into better storytelling, the process is the same—embrace the logic of your creative world and push through until it works.

Thank you for joining me on this journey. If these behind-the-scenes glimpses into the writer's process interest you, let me know. I sometimes worry these details might be boring, but close friends encourage me to share more "day in the life" stories.

I'd love to hear from you—questions, comments, thoughts. Your support means everything as the adventure continues.

What's the hardest creative challenge you're avoiding right now? Sometimes the thing that seems impossible is exactly what we need to tackle next.

Happy Summer Solstice, everyone!

Chris K. Jones

P.S. Special Thanks to Mike Bothwell, who shot and edited my video, and just had a birthday on the Summer Solstice!

I love the peeling back of the curtain on your process, and the backstory to that process. Everything is grounded in self-reflection and your diverse experiences from childhood inventions to judo to Buddhism to being a CFO. Keep up the good work and thanks for including us on your amazing journey!